AKA: Wang Miao’s No Good Very Bad Day

OVERVIEW

Media type: TV show

Streaming service: YouTube (free with ads)

Genre: Sci-fi, thriller, horror

Content warnings: Suicide mentions (I think the record is about five in a minute), cosmic horror

SUMMARY

We open on… what I assume is… supposed to be a representation of an atom? A very boring atom, considering that none of the electrons are moving. Zoom out, to the view of more atoms, all lined up in a beautiful grid. A droplet of water – many droplets of water! The sound effects certainly sound watery. Out, and out, and out… into a glass of alcohol. But not just any glass of alcohol: no, this is a glass of alcohol being drunk by Wang Miao, alongside his new best friend, Ding Yi! That was, like, a minute long. Why… why was that… I’m confused.

Ding Yi asks a couple of questions about Wang’s marriage – apparently he’s been married for eight years, and his daughter (wait, his daughter?) is seven. Ding Yi mentions that he got his hands on his swanky apartment, which is pretty swanky given that it has a friggen pool table in it, surprisingly appropriate for a physicist, in preparation for marriage to Yang Dong, our unfortunate suicide victim from the first episode.

In violation of operational security, Wang mentions the mission from General Chang to infiltrate the Frontiers of Science. Ding Yi has some pretty strong opinions on the group, calling them “a bunch of arrogant idiots” – a stateent that I can’t disagree with.

Title sequence! We’re treated to another surprisingly awesome song – again ith the pool ball motifs, and that odd string of numbers – before the title sequence ends. I like how this piece, in particular, emphasises the odd, almost alien nature of the problem we’re facing, the enormity of the scope of their implications. I also continue to enjoy how the show just refuses to have one single piece of title music, giving us two different tunes in two episodes. As I said in my first Three-Body review, I believe strongly in a good theme’s ability to tie a show’s identity together – which is, oddly, why I think this choice works so well. It shows its identity through showing multiple identities: a tale of trauma driving folks to terrible things, a tale of a man’s breakdown in the face of whatever the fuck he’s going through, a tale of invasion.

We return to Ding Yi’s apartment. That statement comes up again: “physics doesn’t exist”. Wang Miao points out the question that’s been on my mind the whole time: if he drops the book he’s holding, then if physics truly doesn’t exist, then why doesn’t it just float, or even fly off? Ding Yi just drops it. “You’re right. If physics didn’t exist, then Schroedinger wouldn’t be on the floor.” I think we’re going somewhere juicy with this, folks. He makes a terrible mess of his apartment, throwing books about – he’s had a bit to drink, I think. Then, in a wild tangent, he asks if Wang Miao knows pool. Apparently, Yi and Yang Dong liked it because it reminded them of the kind of interactions that go on inside a particle accelerator – actually a pretty neat metaphor. In some ways, it kind of is!

So, Ding Yi puts together an experiment. Clearing the pool table, he and Wang take a series of shots, and in between each, they move the pool table in some way, before the final one returns it to its original spot. This demonstrates one of the key fundaments of science – that of replicability. Theoretically speaking, the laws of physics should hold the same across each instance of the cue ball hitting the other ball, and the ball going into the pocket, no matter its relative physical location or the time. The variables are the same, so you should get the same result.

Ding Yi then conducts a thought experiment: what if you hit one ball into another, and it didn’t go into the pocket? What if it did something… unexpected? The first ball enters the pocket fine, but the second one goes off-kilter, moving off to one side. The third just straight-up flies off the table. The fourth goes nuts, flying around the room like a trapped bird. The fifth instantly accelerates to 99.9999% of the speed of light, going screaming through the pocket, the wall, and off into space so fast that “blink and you’ll miss it” doesn’t even begin to convey just how damn fast it’s going. If you were to try to write the laws of physics based off that, what the hell could you say? You have five experiments, and five completely un-correlated points of data. How the hell are you supposed to do anything anything with that?

You aren’t. That’s the point being made with the pool table thought experiment: you can’t reliably repeat the same experiment and get the same result, thereby ruining your ability to draw conclusions, thereby ruining basically all physical sciences ever. Spooky stuff. Like, legit spooky.

Munphy’s house, several months ago. Yang Dong is there, a police officer is questioning her – did she send these faxes to the man, just before his death? Yang Dong grabs one set hurriedly, almost as if she’s seen something horrifying. Yang Dong points out the time stamps on the faxes, before her experiment took place. It shouldn’t be possible. Wang Miao says so! But we only think it’s impossible. Ding Yi doesn’t know. He’s not supposed to know. He’s supposed to be in the dark, and mildly terrified. If they were taken from the past… and yet, didn’t correlate to any previous data set… one of the fundamental underpinnings of physical sciences just wouldn’t apply.

Miao is shaken. This is a catastrophic development in theoretical physics, he says. Yi proposes that to work in theoretical physics, you need an almost religious belief in what you’re doing, before making mention of a rather odd hypothesis – the shooter and the farmer hypothesis. Miao correctly identifies it as views espoused by the Frontiers of Science, who consistently prove to be bad news. These theories, which can’t really be proven right but also can’t really be proven wrong (thus making them useless as theories, fun fact), apparently give people hope? The kind of hope that is easily mutated, however, into despair. Several months ago, Ding Yi proposes engagement to Yang Dong, offering it as a kind of good luck charm, maybe. Yang Dong just says “the experiment failed”. In best scientific form, Yi suggests just doing some more! Particle accelerator experiments are pretty damn costly, though, all that energy going about, so you’d probably have to get the rubber stamp from somebody with a lot of dosh.

As Miao walks home, he can’t help but think of Yang Dong, and the experimental data she uncovered. The phrase lingers in his mind: “physics doesn’t exist”, “physics doesn’t exist”–until he’s interrupted by a passer-by bumping into him, dropping a beer bottle in the process… which doesn’t hit the ground. He bumps another passer-by, who drops a box, promptly consumed by the ground. Other pedestrians shout abuse at him, but he’s too high to care. As he continues to walk along, he’s accosted by none other than the pool balls, flitting through the air like insects, as he swats fruitlessly at them.

A brief flashback to the 70s again, wherein the mysterious woman at the mysterious base examines a mysterious strip of punched-out tape. Back in the present again, Wang Miao finally decides to visit the Frontiers of Science. Shen Yufei welcomes him, very happy that he’s come! She just wants everybody to get to know the group. According to her, the manor they’re at is owned by a particularly wealthy member of the group – and for sure, it is pretty damn nice! For whatever reason, he offered it to the group as a meeting place. Nice guy. As the tour goes along, the pair stop by a very odd painting…

In his strange vision, probably addled by drugs, the fibres of the painting reach out, almost as if to attack him. Yufei wonders what the hell he’s on. Miao postulates, based on the art, that the manor’s owner is an expert on quantum entanglement, and that the painting is not of Peter Capaldi’s attack eyebrows, a postulation that Yufei confirms.

During the meeting, we discuss the enigmatic shooter hypothesis and farmer hypothesis. Allow me to sum them up for you: say that a marksman fires a bunch of rounds at a target, at intervals of ten centimetres. From the perspective of a two-dimensional society living atop said target, the holes that marksman leaves with his shots would be as natural to them as mountains or valleys are to you and me, but they’d be mistaking the whims of a random guy as an extension of natural law.

In another scenario, say there’s a farm full of turkeys. Every day, at the same time, food is delivered by a mechanism. A scientifically-inclined turkey (shut up, it makes sense in context… I guess) makes repeated observations and declares a law of physics, in the same way that we declare the speed of light and causality. That is, until one day, the farmer shows up, not to feed them… but to slaughter them.

Shen Yufei proposes that we are much like the two-dimensional civilisation, or the turkey scientist, fundamentally unable to grasp the true nature of the universe thanks to our inherently limited perspective. After all, we crawl around on a thin skin of mud and water, atop a mass of molten material, flying around the sun at unimaginable speed, which itself flies around the galactic core at unimaginable speed, and even the galaxy itself moves along, imperceptibly. There’s no way to know what we can’t know, in short. One of those present brings up the problems, irreconcilable, of applying Newtonian mechanics to molecular motion, and the greater issues still of applying them to the quantum realm, pointing to them as examples of the frontiers that this group wishes to probe. He doesn’t understand the point. He only thinks that such discussions serves to make scientists vulnerable – to who or what, we aren’t told – through opening their eyes to the true totality of what they’ll never know. “I will not accept that I’m a turkey scientist!” He declares, in one of the more narmy moments I’ve ever seen in TV. Wang Miao, however, is shocked. He asks Yufei if she’d ever considered that such a statement could kill; she responds, enigmatically, “the turkeys on the farm are meant to die on Thanksgiving Day”.

After Wang Miao leaves the meeting, he’s accosted once again by Shi Qiang. Miao immediately accuses him of manipulating him, prompting him to look into the Frontiers of Science and talk to Ding Yi. He asks if Yang Dong’s death really was suicide; Qiang says that it was, technically speaking, but thinks they might have been somehow provoked. Otherwise, why would there be an investigation? Miao says he’s trying to manipulate him again, this time into investigating Dong’s death, and Qiang pretty explicitly says that he is, even telling him to go to her funeral. After a moment, Miao walks up to the car that this smug motherfucker was leaning on and tries to open the door – but apparently, it’s not his car. He then unlocks it and opens the door, like the dick he is.

Back at the Battle Command Centre, that strange, brutalist building, Qiang reports in: just as planned, Miao went to Ding Yi, and then to Shen Yufei. Chang isn’t very excited by this, but Qiang thinks it’s the start of something, he’d be willing to bet that Miao’s going to attend Dong’s funeral. Qiang does question one thing, though: after months of investigation, and such a large command centre, what have they actually found out? He demands to be read in. Chang wonders if he thinks this means everything in the centre should be reported to him, before reminding Qiang of his job: answer the question of why the scientist killed herself. Qiang makes a demand of Chang in return, reminding him of the deal they made to lift his suspension with the police force. But Chang just says, “have I not already solved it? Are you under suspension? You’re doing pretty well in my department, aren’t you?” This does not seem to please Qiang.

Yang Dong’s funeral. A sombre affair, and rightly so – from what little we know of her, she was a brilliant mind. After the proceedings, Wang Miao approaches Ye Wenjie, the deceased’s mother. He offers his condolences, and they converse about Miao’s research. Miao offers Wenjie a picture he took of Yang Dong as a keepsake, but stops when he notices something strange…

He claims that the development was botched, and promises to deliver a new one in a few days. As Miao leaves, Wenjie returns her attention to Dong’s grave, almost knowingly… there’s something… mildly sus about her, isn’t there? Like she knows something.

As Miao leaves, he’s accosted once again by his new best frenemy, Shi Qiang. Miao makes it pretty clear that he’s not fulfilling some agenda of Qiang’s, he’s just there to pay his respects and offer condolences. Qiang doesn’t care, he certainly didn’t ask Miao to make it clear. But, Qiang couldn’t help but notice that Miao and Wenjie talked for a while. Not too long, but definitely more than “I’m sorry for your loss”.

Back home, Miao examines the photo with the weird numbers. They’re surely weird numbers. Confused, he phones his photo developer, who is equally confused. Upon a closer examination, it turns out that the photo negative has a number stamp on it, too. Whatever’s doing this, it’s gotta be in his camera. His… 1980s camera. With absolutely no ability to insert a string of numbers into a photo. Beautiful thing, though!

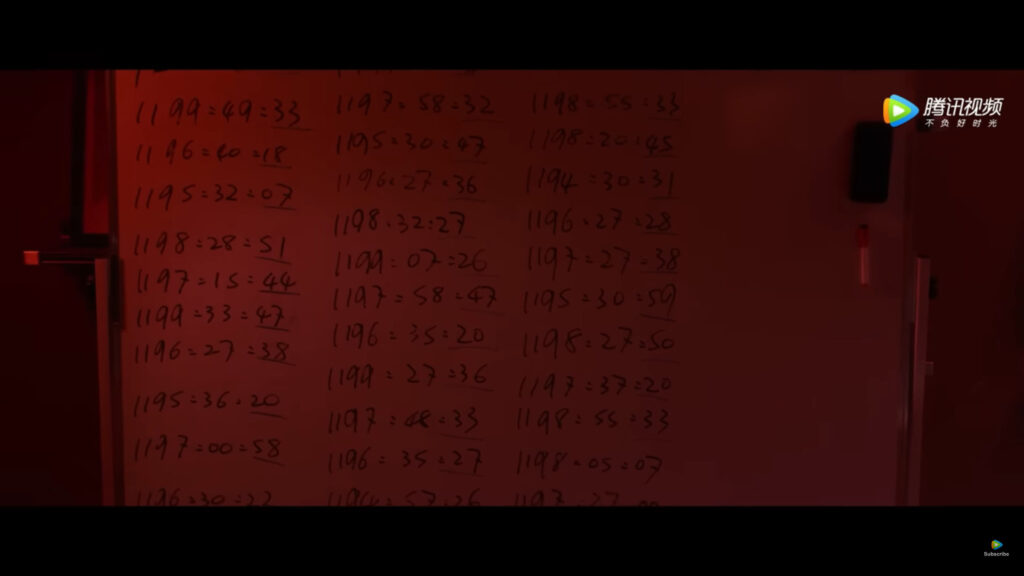

Further investigation of photos taken since reveals that the codes change. How many pictures left in the roll? But then why would it be on the film? Surely that’d ruin the picture. Being the good scientist he is, he records every last number from every last photo he can find, looking for any correlation. With every last one written down, it almost looks like…

Time. Perhaps, some kind of… countdown. A countdown showing 1,194 hours – just under 50 days. Is that when Thanksgiving is? It can’t be that close to Thanksgiving if it’s summer in 2007. Determined to find out more, Wang Miao goes around his apartment and takes pictures of various objects. Then, with the equipment and chemicals in his darkroom, he develops the photos, investigating each for that mysterious time code. And surely enough, each has it, right in the middle of the picture, without variation. As an aside, I love how they’re showing off the process of developing a photo here. The chemistry behind photo development has always fascinated me – and apparently my dad used to develop his own photos with his father, too, so I get it from somewhere, apparently.

After a short montage, we return one last time to Yang Dong and Ding Yi, outside the house of the late Professor Munphy (late for what? His own funeral?). Ding Yi tries to rationalise the contents of the documents found. “Nobody could have gotten the results of your experiment before you conducted them,” he tries to reassure her. It has to be a glitch in the Matrix–er, photocopier. But could a photocopier make a mistake with only the time, and be otherwise perfect? It’s just not possible.

Episode end.

I've seen things you people won't believe Soon, my planet will vanish I've known the future you people won't think of Soon, your planet will be punished

DEE’S THOUGHTS

Oh boy. Oh boy. So, this is a very, very juicy story – touches on some scary ideas… except they aren’t scary. Let me tell you why.

So, I’m sure you’re all familiar with the simulation hypothesis – the one that Musk loves talking about, how we’re all in a simulation. Fundamentally, it’s exactly the same as the shooter hypothesis and the farmer hypothesis, posited by the Frontiers of Science. They all posit that our physical laws are artificial, created by some higher power. The how and why doesn’t really matter, here.

The big issue is twofold, and all three share them: firstly, they’re unfalsifiable – in other words, you can’t definitively prove them false. Any time you manage to prove it, some guy could come up and say “but actually” and before you know it, the goalposts are a mile down the road. You can understand that this might not be conducive to good science, I hope.

The second issue is that their proposals don’t actually matter. They only explain what we have already observed by experimentation. Even if people stick to the Earth because of Ultronian Superglue #2 instead of gravity, we observe the effects of Ultronian Superglue #2 as gravity. As far as we can experimentally tell, they hold up. Their predictions tell us about the world. It doesn’t matter if they’re consequences of natural laws, or defined by some shooter/farmer/programmer, they explain our world, and thus are still relevant. In short, the ideas proposed are only scary because you make them scary. As soon as you look at them in another light, they’re a scientific curiosity and nothing more.

There is, however, an interesting way to explain why the phrase “physics isn’t real” is what it is, though, in the pool ball metaphor we see. One of the fundamental underpinnings of science – repeatability – is being somehow toyed with, as evidenced by Shen Yufei having access to experimental data that varied from predictions before the experiment occurred. The anomalous results we see in particle accelerator experiments are essentially random, but somehow, Yufei has access to them. For all intents and purposes, 2+2 is no longer equal to 4, and somebody can predict, in advance, what it’s going to equal today. That’s the real horror here.

I still wouldn’t have described it as physics not existing anymore. There has got to be a better way to phrase it than that. Turn on your location, Cixin Liu, I just want to talk!

Overall, I’d give this episode… the rejection of turkey science out of ten.

Fun fact: when I was watching this episode with my family, my stepmum proposed that the early results could somehow have been brought to Professor Munphy by time travel. While this isn’t that kind of show, I’d like to offer my sincerest congratulations on a non-sci-fi fan understanding the genre well enough to propose a potential solution based on previous exposure to sci-fi tropes. Suppose ten years of dealing with two gigantic fucking nerds like me and my dad will do that to you. If you’re reading this, I love you, stepmother whose name I shall not mention for privacy reasons! And since I know you’ll be reading this, Dad, tell her I said that!